Would you consider yourself an “indoors” or “outdoors” person? While some people feel totally at home in the great outdoors, most of us spend the majority of our time inside our actual homes. Regardless of your comfort level on this spectrum, we’d like to suggest spending just a little bit more time outside this spring. The healing power of nature is real, and could be an easy support to add to your mental health journey.

Scientists estimate that the average American spends about 93% of their life indoors [1]. The average time spent outdoors differs between California and Alaska by only 2 mins per hour, per person [1]. These numbers suggest that it is not weather or daylight hours keeping us indoors, but comfort, culture, and priorities.

There are statistics and scientific explanations for the links between inactivity and mental health, lack of sun exposure and mental health, and time in nature and mental health [2-4]. We’re going to show you the data and help you make sense of it. We think this might help motivate you to get outside and absorb the healing power of nature.

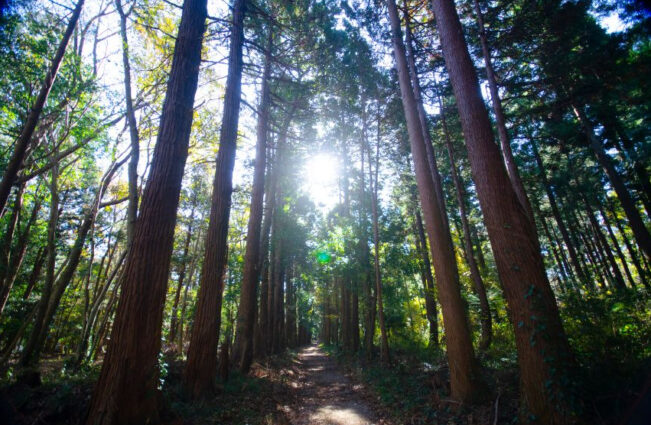

Shinrin-Yoku or “Forest Bathing”

In Japan, there is a practice known as shinrin-yoku. Shinrin means “forest”, and yoku, “bath”. Shinrin-yoku means spending time taking in the forest through all of your senses. In some Japanese forests, there are forest therapists who guide forest bathing experiences based on physical and psychological assessment.

Maybe you don’t have access to a forest therapist, or even a forest. But, you can still practice the basic elements and gain benefits of forest bathing.

The basis of forest bathing is being present in nature and noticing all aspects of the setting. What do you see, smell, hear, and feel on your skin? By paying attention to all of these neutral, calming elements, you can start to let go of stress and worries associated with technology, urban life, and social relationships.

Much like meditation, forest bathing is all about being present in the moment. Try turning off your electronic devices. Try not to focus on a destination. Maybe you aren’t in the mood to wander, or your “forest” is a park too small for hiking. You can still forest bathe sitting or standing in one place. Perhaps you like to practice yoga or tai chi. You can incorporate these practices while taking in the sensory offerings of a forest too.

Respect for the healing power of nature isn’t unique to Japanese culture. In modern Germany and Austria, adults often take part in a health practice or “Kur” that includes a break from work to focus on mental and physical health. A Kur is likely to include nature walks, swimming, and mud bathing, based on a doctor’s recommendation.

The Specifics: maximizing the benefits of being outdoors

What is “nature”?

All you need is a place with trees to forest bathe. Yes, just being in the sunlight can have a positive effect on your mood through vitamin D production and stimulation of the pineal gland. But, standing outside isn’t what we mean when we talk about the healing power of nature.

To maximize the benefits of being outdoors, you really need to find a green space in “wilderness”. While the definition varies, generally, “wilderness” is a place with species diversity and minimal human intervention. Try, if you can, to choose broadleaf woods, parks that feature water, and areas with significant biodiversity (many different types of living species thriving together). These spaces have been linked with greater health benefits [5-7].

While sitting in front of “simulated nature” (or staring at photos or videos of a forest environment) can be somewhat calming when you are suffering from stress or burnout, it doesn’t elicit the same feelings nor the same biological response as the real thing [8].

How does it work?

Science can’t yet fully explain why being in the forest calms us, but it does, and there are many avenues through which it may be happening. We will describe a few of those hypotheses.

ART

One theory relevant to mental health and mood is called the attentional restoration theory (ART). It explains that our home and work environments have an excess of “bottom-up stimulation”. In those settings, we must choose to simultaneously ignore distractions and concentrate on specific stimuli in order to complete our tasks. This type of focus is stressful in and of itself, and over time leads to cognitive fatigue [9].

In contrast, natural environments do not demand any sort of compartmentalization or prioritization. They elicit “soft fascination” meaning that whatever triggers feelings of pleasure can be the focus of our attention.

In other words, we don’t have to concentrate or focus to enjoy nature. You can rest while passively noticing the sound of leaves rustling, feeling humidity on your skin, or smelling fall in the air.

ART suggests that spending time in nature actually restores our energy and ability to focus on a demanding task when we return to work or school [9].

Bio-what?

The ‘biophilia hypothesis’ proposes that all humans have an intrinsic affinity to other species and nature because interaction with the natural environment drove the evolution of our species [7]. Basically, human DNA just codes for us to feel calmer in wild spaces. Under the biophilia hypothesis, people are expected to prefer biologically diverse environments when we are trying to recover from physiological stress or mental fatigue [7]. In response, that time in nature assists the restoration of our ability to focus [7].

The ‘biodiversity hypothesis’ suggests that exposure to biodiversity (many different types of living organisms thriving together) improves the immune system by regulating the species composition of the human microbiome [7]. Under this hypothesis, exposure to beneficial microbes in the forest environment leads to better mental health of the human host.

There must be something in the air…

Another calming factor may come from inhaling aromatic compounds from plants called phytoncides. Plants release these compounds for protection from fungi and bacteria. In the human body, phytoncides can support healthy blood pressure, robust immune function, promote relaxation, and improve sleep [10,11].

The air in forests, mountains, and around moving water also contains high concentrations of negative ions, which have been shown to support a balanced mood and improved cognitive function [12].

How can you measure the healing power of nature?

If you are a data-minded person, you may be wondering “how do we know nature supports mental health?” This is a good question. Yes, many studies on nature and mental health are based on surveys and self-reported serenity levels, but not all.

Stress reduction can be measured quantitatively through levels of cortisol, other adrenal/stress hormones, and certain inflammatory markers in the circulation or saliva. Pulse rate and blood pressure are also often associated with stress level, when compared to a baseline, and these data are collected in some studies.

This is to say, there is hard science involved in these claims.

A Japanese study reported significant stress reduction in male college students after just 30 minutes of forest bathing [13]. Students were assigned to walk for 15 minutes and then sit for 15 minutes in either a forest or a city area. Compared to the city, those who walked and sat in the forest had significantly healthier blood pressure, pulse rate, and salivary cortisol concentration. All biological markers of stress reduction.

An even larger study showed circadian cortisol cycles (a person’s normal fluctuations in stress hormone levels) are significantly affected by the amount of time they spend in nature [14].

Are the benefits of forest bathing really just from exercise?

Exercise is a well-supported avenue to promote mental health, but you don’t need to elevate your heart rate to receive benefits from time in nature. It really is about “just being”.

In terms of quantitative data, one study showed that two, 2-hour forest walks on consecutive days increased the number and activity of natural killer T cells (beneficial immune cells) by 50 and 56%, respectively [15]. Those activities remained significantly boosted for at least a month after returning to urban life [15]. Similar length walks in an urban environment did not elicit the same effect.

We would be remiss not to mention the opportunity to double-dip the mood boost. While a forest bath isn’t about exercise, if you can walk or hike *wherever* it will likely have a positive effect on your mood [16]. It’s science.

We hope this information gets you outside this spring to enjoy the healing power of nature. It’s little changes to a regular routine that can make a big difference in your mental health. And you deserve it.

References

- https://www.nature.com/articles/7500244

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022399920308540

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1011134410001879

- https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06400.x

- https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jpa2/26/2/26_2_135/_article/-char/ja/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272494410000496

- https://academic.oup.com/bmb/article/127/1/5/5051732

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272494410000204

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01178/full%C2%A0

- https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/bitstream/handle/10755/21955/Article.pdf?sequence=1

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01093/full?fbclid=IwAR1znfQksYd8QcE9j3AM_TN7LxNEQlz3ekXPwdDX9JTfKCXwYcXfqqOJHV8

- https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/cmc/2021/00000028/00000013/art00005

- https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jpa2/26/2/26_2_135/_article/-char/ja/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169204611003665

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12199-008-0068-3

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1755296612000099